How I Came to Know My Father ~ Part 4

by Sally T. Grove

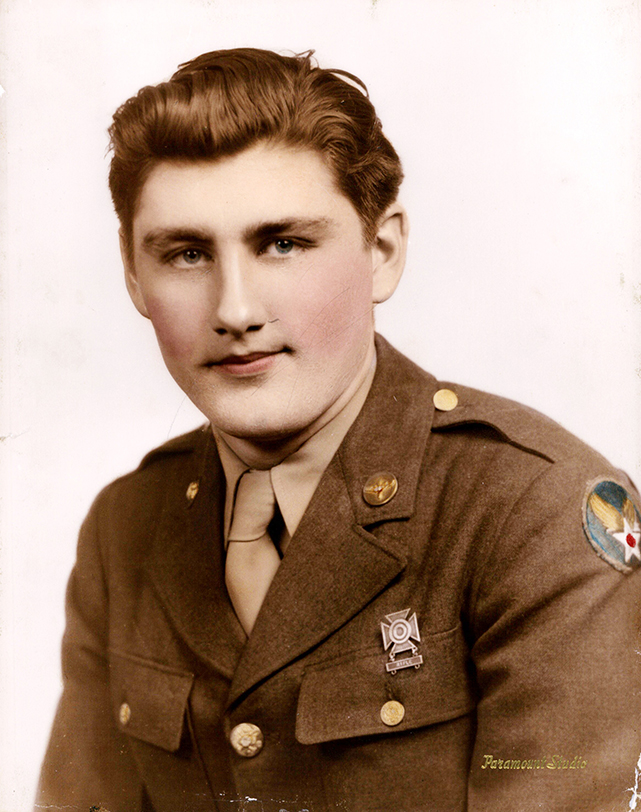

Courtesy Photo of Chester L. Grove, Jr. in Uniform

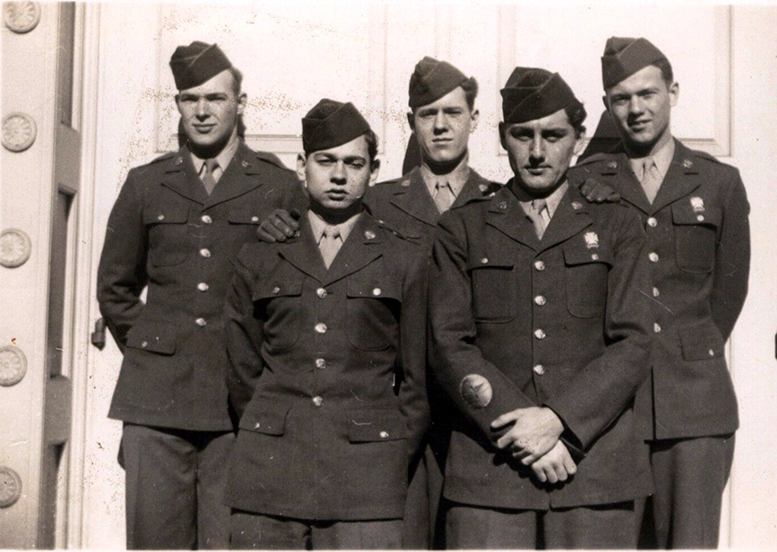

Courtesy Photo

I started to understand my father, Chester Grove when I was 20 years old in 1977. That’s when I found the journal he kept during World War II. I read about experiences he didn’t talk about…fighting in war.

A cold March rain came to add to our discomfort…my arm was now stiff but the bleeding had stopped. My buddy’s head and legs were giving him plenty of trouble…we had to slow the pace and take turns helping him along…we often went through the forest on trails and dirt roads, tanks and guns concealed in the forest…we were constantly wet and chilled.

Our guards stopped at a house in the next town and ate while our stomachs just growled with hunger. At 4:00 p.m. we came to a little German town and sat down while the guards talked to a German captain. We had been walking since 5:00 a.m. and we were a tired and hungry bunch of Joes…

Dad had been going for at least 20 hours straight. I doubt anything that life dealt my father after the war could compare with what he had experienced in Germany. No wonder my father was always grateful for the small blessings in life. He taught us to stop and savor the view, to hear the calls of Bob Whites and Whip-Por-Whils echoing in the air at sunset, and to know that in our family we were rich beyond money.

...one at a time into the house… the Jerry’s captain interrogated us… I was next to be questioned and was glad my time had come, for the uncertainty of waiting was terrible. I went into the room and the officer behind a large desk asked, “What’s your name?” I answered with my name, rank and serial number. He then asked my outfit. I wouldn’t answer so he told me the answer, the division and also the regiment I was from… I was not surprised that he knew the division but I was given a great surprise when he also named the regiment. I still cannot understand how he found out unless he forced one of the fellows to talk (which I doubt) or found the answer on a letter or paper of some kind someone was carrying. He then asked whether we were Panzer’s troop, flyers, or infantry, and I guessed then that he didn’t know much about our outfit. I refused to tell him and he got very mad and threatened to hit me unless I talked. He even drew back his arm in a motion to strike me but it turned out that he did not strike. I was very mad when he threatened me and I’m sure that if he had struck me I would have gone over the desk after him and killed him, for I know I could not have taken a slap without fighting back. It is good that he didn’t for I surely would have been killed if I had tangled with him.

I cannot even imagine my father having the thought of killing someone. He was the gentlest soul I have ever known.

After he had finished questioning all of us, he said that since we would not talk we would have nothing to eat until we decided to talk… We waited for about two hours in the rain and cold March wind, while the guards ate and we looked on with watering mouths and hungry eyes. Finally we were told to go in the house… we were brought in a small bowl of cold potatoes, about one apiece. But they vanished in a flash, serving only to sharpen our hunger.

Dad hadn’t eaten since 8:00 p.m. the night before. He had gone 24 hours without food.

About half an hour later, the three of us that were wounded were told that a truck was waiting to take us to a hospital and the rest would march on to the concentration camp. I almost wished to go on to the concentration camp rather than split up with the rest of the fellows, but I wouldn’t have been allowed… so we parted our little group that had been through so much together.

What would have happened had he gone to the concentration camp? Would things have turned out differently? Thank God his life took the turns it did or I would not be here to tell you my father’s story.

It was dark and we rode for ages in the small truck and went through countless towns. Finally, about 11:30 p.m., we were taken into a large German house, which was being used as a Jerry field hospital. We gave our name, rank, and serial number to a Jerry orderly at a desk and then sat down among half a dozen wounded Jerries to wait our turn with the doctor. I was taken into a room equipped for operating. A radio was playing an American song. The first American music I had heard for months… A beautiful, young blonde-haired girl was helping the doctor. He told me it was his daughter. I laid on a table and was stripped to the waist then strapped down hand and foot. The doctor drew out a large scalpel and laughed as he drew it across my throat in a motion to cut it. If he had not been laughing, I would have been very much afraid, but I knew it was a joke so I laughed back.

My father had a great sense of humor, a gift he gave us all. We still laugh when we think about Dad learning to play tennis. For all of our lives, my father came home from work and changed from his suit into blue jeans. Blue jeans were his primary play clothes. So, when Dad played tennis, he played in jeans. That was fine in cool weather, but when the mercury skyrocketed along with my father’s passion for tennis, the problem had to be fixed. For Father’s Day, my siblings and I bought Dad tennis shorts. My father appeared in the hallway, boxers hanging inches below the shorts. Being a time before it was chic to have boxers showing beneath shorts, the whole family dissolved into laughter. Dad not only graduated to shorts that summer, but was introduced to briefs as well.

The doctor said, “Don’t feel so good now do you?” He told me in broken English that he had studied medicine in Chicago and I felt a little better.

Sadly, this is where Dad’s war diary stopped. He didn’t explain how long he was held captive, when he was liberated from the Germans, where he recuperated from his wounds, or when he returned to the states. Thankfully, my father had lived through these horrendous events and lived to write a part of his story.

Slowly, after reading the last page, I closed the stenographer’s notebook. Dad was a writer. This was my father but outside the lens of my experience. Were his memories too horrible to speak? Did Dad write this journal to have an outlet to express his feelings, hoping that in the writing of the words, the horror would be erased from his memory?

My mind’s camera had always framed a gentle, quiet man. The man I had known came home each afternoon by 4:30. He took a nap, his eyes closing and his body surrendering to a fast, deep sleep, the very moment his head made contact with the mattress on my parent’s carved-pineapple post bed. As kids, we rushed to see Dad when he came home; if we were two seconds late, our sharing had to wait until dinner at 5:00.

I clutched the notebook to my chest, my heart racing as I slowly ascended the stairs. Now that I knew all of this, I could not pretend that I didn’t know.

I opened the door and found various members of my family sitting around our house. I relaxed my grip on the notebook, looked at my mom and each of my siblings, knowing that I knew what they did not. I don’t remember how it happened, but I shared Dad’s notebook with my family that day.

You see, my father died when I was twenty, the day after Thanksgiving. He had gone hunting, fell out of a tree stand, and hit his head, dying instantly.

I remember vividly, too vividly, the night that my father’s station wagon, along with another car, pulled into the driveway and my Aunt Kitty got out and walked to the door. I assumed that Dad had finally gotten his deer.

When, in anticipation, I opened the door to my aunt and uncle, I knew that I was wrong. Their faces said everything. I don’t know how I held it together that night. I told my aunt I would tell my mother when she returned home from her quick grocery run. Somehow, my family made it through the night, and the days and nights that followed.

The next day, the day after my father died, I would descend the stairs to the basement. I would go through my father’s belongings, wanting so much to touch him, to hear him, to know he was there. I would open a trunk and find a small stenographer’s notebook, its brown cover worn, well-traveled, the edges frayed—my father’s war diary.

I would learn things about my father that I had never thought to ask him. Some questions to this day remain unanswered. Still, the journal provided me a glimpse into a man I did not know, and it is how I came to know my father.