Old-time accomodations

along the c&O Canal

James Rada, Jr.

When the brass horn would sound at all hours, day and night, the lockkeepers of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal would leave what they were doing and head for their lock. No matter the weather outside, their job was to set the lock for the approaching canal boats.

Each lock would lift or lower a canal boat around 10 feet as the canallers hauled coal and other cargo down the Appalachian Mountains from Cumberland, Maryland, to Georgetown and back.

Nowadays, most of the canal is just an empty ditch, but many of the canal houses remain. Carol Patch of Arlington, Virginia, hosts an evening dinner party at Lockhouse 10 once a year for her friends. It is one of six lockhouses available for rent along the C&O Canal.

Lockhouse 10 is decorated as it would have been in the 1930s, so it has electricity and indoor plumbing. However, the kitchen equipment certainly doesn’t include a microwave and dishwasher.

“It reminds us of how hard our mothers had it,” Patch said.

A Lockkeeper’s Life

A C&O Canal lockkeeper had to be on the job whenever the canal was open, an average of 10 months a year. For this, they were paid a small salary based on the number of locks they tended, given a plot of ground on which they could plant a garden, and a lockhouse in which to live.

The C&O Canal has 74 locks that raise and lower boats. As a canal boat approached a lock, the canaller would call out “Heeeeeey, lock!” or blow a horn. The lockkeeper would come out and make sure that the lock gates were open for the incoming boat.

For instance, if the boat was moving downriver, the mules would pull the boat as the captain steered it into the lock. Ropes were tossed ashore and wrapped around snubbing posts (thick logs set in the ground). The slack was taken up on the ropes to act as a brake on the canal boat to keep it from crashing into the opposite set of lock gates, which were closed. The locks were built barely large enough to contain the 92-foot-long and 14-foot-wide canal boats. Once the boat was stopped inside the lock, the lock gates behind the canal boat were closed.

Lock gates were designed so that they formed a point upriver when closed. In this way, water flowing against the gates helped keep them closed and sealed. Sluice valves at the bottom of the downriver lock gates were then opened with large rod-like keys. Water from inside the lock flowed out of the lock through the sluice valves. Since the upriver gates were closed, the water level inside the lock slowly fell.

As the boat was lowered, the ropes around the snubbing posts were gradually let out. By maintaining tension on the ropes, the boat could be stabilized somewhat so that it wouldn’t bounce around inside the lock and either damage the lock or the boat.

When the level inside the lock matched that outside of the downriver lock gates, the sluice gates were closed and the downriver lock gates opened. The mules pulled the boat out of the lock to continue its journey downriver.

The entire process of locking through took about 15 minutes.

Canal Quarters Program

Of the 76 lockhouses built to help run the canal, only 20 remain. Of those 20 lockhouses, 6 can be rented for a night as part of the C&O Canal Trust’s Canal Quarters Program.

“It’s a partnership between the C&O Canal Trust and the National Historic Park,” said Heidi Schlag, director of communications for the C&O Canal Trust. “The park was looking for a way to preserve the lockhouses, and we were looking for a way to help the park.”

The program began in 2009 when the Canal Trust and National Park Service restored three different lockhouses to different periods of time along the canal. Some had amenities. Some were considered rustic.

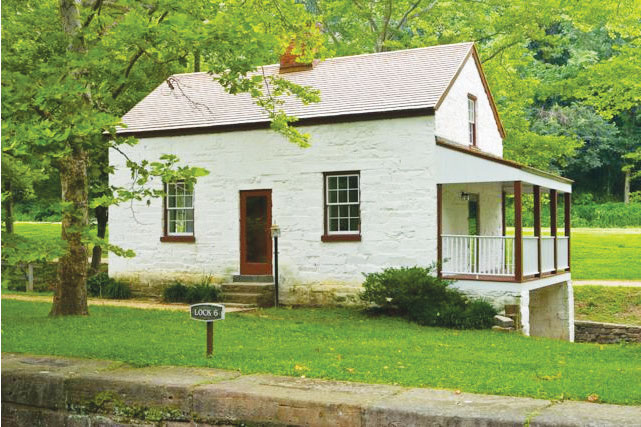

“Lockhouses 6 and 10 are the ones with amenities, and they are very popular,” said Schlag. “You usually have to book them six months in advance.”

The lockhouses with amenities have heat, air conditioning, electricity, and running water. People who stay in the rustic lockhouses have to use a porta-john for a bathroom and an outdoor hand pump for water. It may seem odd that someone would want to stay in such a place, but it gives the guests an idea of what life was like for a lockkeeper and his family during the particular time period to which that lockhouse has been restored.

“I kind of liked washing using a pitcher and basin,” said Elaine Stonebraker. She has stayed in five of the six lockhouses that are available to rent, including staying in her favorite one three times. She lives in Southern Maryland and has to drive two hours to reach the canal.

Two lockhouses are currently handicapped accessible.

Visitors can also find interpretive information, such as panels and scrapbooks, in the lockhouse that explain what was happening on the canal during the particular time to which the house has been restored. Stonebraker likes to read the stories collected in the scrapbooks, many of which feature people who used to live in that particular lockhouse.

The first lockhouse that Stonebraker stayed in was Lockhouse 6 because it was the closest one to where she lived. She loved her night there so much that she started looking for chances to stay in other lockhouses.

“They’re great,” Stonebraker said. “You are actually experiencing history. You are staying where someone lived, where children were brought up. You can imagine working the lock.”

Patch, on the other hand, lives near the canal and found that it’s a convenient place for her to hold her dinner parties. She discovered that she could rent Lockhouse 10 when she was walking along the towpath one time. When she learned that a friend of hers was on a Sierra Club hike and would be passing along on the towpath early in the morning, she decided to rent the lockhouse. That way, she could hold her dinner party, stay the night in the lockhouse, and be up early in the morning to greet her friend as she came hiking along the towpath.

What the Future Holds

The Canal Trust opened its seventh lockhouse for overnight stays in 2017. This is Lockhouse 21 at Swain’s Lock. The lockhouse gets its name from the Swain family that occupied the house for generations, first as lockkeepers and then as a NPS concessionaire. The stone lockhouse is 32 feet by 18 feet and will have amenities.

One of the lockkeepers who used to live there was Jesse Swain. Someone once gave Swain a two-day-old gosling. Swain named it Jimmy and he raised it as a pet. It lived to be 27 years old. Jesse and Jimmy were fixtures on the canal for years.

“My father would get in the buggy to go to the Potomac store, and Jimmy would get right up beside him and ride out there and back,” Otho Swain said in an oral history in Home on the Canal. “If my father would go fishing in the boat, Jimmy would get in the water and swim right out to him and stay out there as long as he stayed. Anybody’d go around my father, Jimmy would bite the devil out of him.”

The Canal Trust also wants to restore other houses on the canal.

“The plan going forward is to eventually have enough canal houses that a visitor can have a hut-to-hut experience traveling along the entire canal,” explained Schlag.

The Restored Lockhouses

Lockhouse 6 is at mile marker 5.4 near Brookmont, Maryland, and has full amenities. This lockhouse is furnished to appear as a lockhouse in the 1950s would have appeared.

Lockhouse 10 is at mile marker 8.8 near Cabin John, Maryland, and has full amenities. This lockhouse is furnished to appear as a lockhouse in the 1930s would have appeared.

Lockhouse 22 is at mile marker 19.6 near Potomac, Maryland, and is a rustic house. This lockhouse is furnished to appear as a lockhouse in the 1830s to 1840s would have appeared.

Lockhouse 25 is at mile marker 30.9 near Poolesville, Maryland, and is a rustic house. This lockhouse is furnished to appear as a lockhouse would have appeared during the Civil War.

Lockhouse 28 is at mile marker 48.9 near Point of Rocks, Maryland, and is a rustic house. This lockhouse is furnished to appear as a lockhouse in the 1830s would have appeared.

Lockhouse 49 is at mile marker 108.7 near Clear Spring, Maryland, and has electricity only. This lockhouse is furnished to appear as a lockhouse in the 1920s would have appeared.